The Whangaparaoa Story

Sometime prior to 800AD, New Zealand was discovered and settled by Polynesian people who had travelled on epic voyages from the group of islands known today as East Polynesia.

They were the descendants of an ancient culture which originated in South East Asia some four thousand years ago.

Several of the voyaging canoes from Polynesia extensively explored the New Zealand coastline and systematic migration and colonisation of the new land, Aotearoa New Zealand, took place over a number of generations until around the 14th century.

It is believed at that time that the two canoes, Tainui and Arawa which travelled south in the great migration found a dead whale on the beach where they landed in East Cape and fought over it. This is where the original name Whangaparaoa (Bay of Sperm Whales) originated. The Tainui canoe subsequently travelled around much of the New Zealand coastline as far as North Cape before returning to Tamaki and it is believed they may have named the northern Whangaparaoa. Certainly, this name has been in use since before early European contact.

The area around Whangaparaoa is well renowned for its abundance of fish and sharks and strandings of various types of whale were not uncommon. In 1925 a 27-metre blue whale was stranded on Orewa beach.

The peninsula was on the direct canoe route between Northland and Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland), two regions heavily settled by Maori tribes in pre-European times and so was of strategic importance.

Nga Oho was one of the earlier tribal names used by the Tamaki Maori people who descended from the lengendary Tainui navigator Rakataura (also known as Hape).

Ngā Oho resided mostly around the North Shore region and their rohe (tribal boundary) once spanned from Cape Rodney/Okakari Point near Leigh to Tauranga.

Close relations of the Nga Oho were the Te Kawerau a Maki who are the tangata whenua (people of the land) of Waitakere City. The Kawerau a Maki people have been a distinct tribal entity since the early 1600s. Maki and a large group of his Ngati Awa followers from Taranaki migrated northward to the Auckland isthmus. Ultimately Maki and his people conquered the Auckland isthmus and the land as far north as the Kaipara harbour. The people of Waitakere retained the name of Te Kawerau a Maki as their tribal name. Other descendants of Maki adopted their own tribal names.

As Maki and his brothers Mataahu and Maeaeariki spread their influence north one of numerous battles was at Whangaparaoa Peninsula, where the Ngaoho people were defeated and absorbed by intermarriage.

Maeaeariki eventually made his home at Orewa while his children Te Utu and Kahu remained at Whangaparaoa residing in what is now Shakespear Regional Park. It is from Kahu that the sub-tribe of Te Kawerau, who occupied the Whangaparaoa district until the 19th century took the name Ngati Kahu.

Intertribal relationships, peace settlements and marriages with Ngati Whatua, a tribe from the southern Kaipara, enabled Ngati Kahu to live in peace on their lands at Orewa, Whangaparaoa and Okura for over a century.

However, in the mid 1700s, Ngati Kahu began to be affected by the movements of tribal groups in the surrounding regions. Pressure came particularly from the Hauraki tribes of the powerful Marutuahu Confederation which wanted to control the important shark fishing grounds lying off the Whangaparaoa Peninsula.

Fighting between the Marutuahu tribes and the Kawerau iwi continued sporadically throughout the 18th century. By the 1780s, the Hauraki tribes were in the ascendancy. Ngati Kahu still remained in control of the Whangaparaoa district, although the Ngati Paoa iwi had shown their dominance by constructing a small pa on the adjoining island of Tiritiri Matangi for use while on fishing expeditions. They sought control over the famed tauranga mango, or shark fishing grounds, of the coastline north of Whangaparaoa. From these grounds, thousands of sharks could be caught and dried in summer and then taken home to the Hauraki Gulf to provide a valuable winter food source. Ngati Kahu had their own pa, Rarowhara, and camping area related to the sharking grounds at the northern mouth of Weiti River.

Rarowhara pa is located at the heel of the Whangaparaoa Peninsula to the east of the Weiti River in the area now known as Arkles Bay.

Ngati Kahu and Kawerau had defeated Ngapuhi in the 1790s at Waiwhariki.

Warfare continued between the two groups until the 1790s, when a major peace-making meeting was held at Mihirau in what is now the Wenderholm Regional Park. This fragile peace was soon broken and the Marutuahu iwi inflicted a major defeat on the Kawerau people at Whangateau near Omaha. Ngati Kahu people assembled at Rarowhara Pa. Mereri, a Kawerau elder living at Awataha village in the early 1900s, told of the events which followed: ‘The Ngati Paoa ultimately attacked our people in the pa at Rarowhara, near Matakatia but we surprised and defeated them on the beach in open battle. Thereafter we held those places at Whangaparaoa peninsula and Te Weiti river until Nga Puhi attacked us’. This was in 1821.

Another early history version that has come down through the ages is the ancestress Mahurangi, who was a tohunga (priestess) who lived in Hawaiiki and whose powers are said to have enabled the construction of the great voyaging waka Tainui.

It is believed the Tainua waka originally arrived at what is now known as Wenderholm Regional Park in around 1200 and they gave the name Mahurangi to a small island adjacent to the Maungatauhoro headland. The islands' name gave rise to the harbour in which it sits, and eventually to the wider district and the Crown's land purchase.

Subsequently, Ngati Kahu had a number of settlements for protection along the Peninsula at –

Te Haruhi Bay Kainga - The bay's Maori name of Te Ha-ruhi means weak breath referring to the sheltered nature of the bay. The local tribe, the Ngati Kahu, cultivated the lands here growing kumara, gourd, yams and taro in the fertile fields close to the bay. Their settlement stretched across the peninsula to Army Bay on the north of the narrow isthmus and middens, cultivation terraces and kumara storage pits are found across this section of the park.

The settlements were defended by 5 pas, the best preserved and accessible being Shakespear Homestead Pa (see mention later). In addition, a burial site with finds including hangi stones (heated stones buried in an earth oven to cook food) is now a protected place by the campsite at Te Haruhi Bay. Some sites are located on the Ministry of Defense land at the northern boundary of the park and are not accessible to the public.

Rakauananga Pa is a hillfort located on a promontory above Hobbs Bay at Gulf Harbour. The pa is located at the eastern headland of Hobbs Bay. The site has good views west towards the major pa and settlement of Rarowhara Pa at Arkles Bay and would be the main defensive pa west of Shakespear's kainga (settlement) and pas to the east.

Coalminers Bay Headland Pa - This Headland Pa is located above Coal Mine Bay on the north side of the Whangaparaoa Peninsula. The pa site has a commanding view of the coastline with fine views down to the pretty sandy beach below.

Little Manly East Point Pa is located at the north eastern end of Little Manly Beach. The pa has extensive views south towards Rangitoto Island and today’s Auckland city, and to the west towards the Weiti River and the south western end of the Whangaparaoa Peninsula along which 2.5 kilometres away is the important Rarowhara Pa site.

West Pa Manly is a Headland Pa (Maori hillfort) located above the west end of Big Manly Beach. The pa commands a fine view of the coast to the east, west and north from where hostile canoes might come.

In September 1821 a large Ngapuhi taua (war party) came south to avenge their defeat. Hongi Hika was leading an expedition against Te Hīnaki of Ngāti Pāoa at Mauinaina pā, on the Tāmaki isthmus, and subsequently moved on to attack Ngāti Maru at Te Tōtara pā, near present day Thames. The heavily armed northern tribes attacked those to the south, who had few or none of the new weapons.

Ngati Kahu, along with the surrounding Kawerau iwi, gathered in Rarowhara Pa but were heavily defeated. Tribes who had only heard of these terrible weapons lived in great fear. The survivors of Ngati Kahu fled inland to the Ararimu Valley (adjoining Riverhead Forest) where they lived for a time, only returning periodically to Whangaparaoa. Ngati Kahu lived in exile near Muriwai and then, after Ngapuhi defeated a combined Ngati Whatua force at Te Ika a Ranganui near Kaiwaka, they fled to the Waikato where they lived in exile for nearly a decade (1820-1830).

A few Ngati Kahu gradually returned to the Whangaparaoa district. Through the 19th century Ngati Kahu migrated over their ancestral domain between Orewa and Okura in a seasonal cycle of fishing, hunting, gathering and harvesting. They maintained kainga, or occupation sites, throughout this area although settlement was concentrated around the sheltered bays on the southern coastline of the Whangaparaoa Peninsula, and in particular at Te Haruhi Bay because of its strategic location and its abundant natural resources. It also provided the best site for cultivation in the Whangaparaoa district.

In 1876 Paora Tuhaere who was the paramount chief of Ngati Whatua who was also of Ngati Kahu descent tried to lease part of the land at Te Haruhi “as a place where we may cultivate and near a fishing ground for sharks”. The old kainga (village) is now part of Shakespear Regional Park.

Other than this the region was almost totally deserted of human habitation for a long period of time.

European History

The first European to arrive in New Zealand was the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman in 1642. The name New Zealand comes from the Dutch ‘Nieuw Zeeland’, the name first given by a Dutch mapmaker.

A surprisingly long time passed — 127 years — before New Zealand was visited by another European. The Englishman Captain James Cook arrived here in 1769 on the first of 3 voyages.

European whalers and sealers then started visiting regularly, followed by traders.

By the 1830s, the British government was being pressured to reduce lawlessness in the country and to settle here before the French, who were considering New Zealand as a potential colony.

On 6 February 1840 at Waitangi, William Hobson — New Zealand’s first Governor — invited assembled Māori chiefs to sign a treaty with the British Crown.

The treaty was taken all around the country — as far south as Foveaux Strait — for signing by local chiefs. More than 500 chiefs signed the treaty that is now known as the Treaty of Waitangi (Te Tiriti o Waitangi).

Māori came under increasing pressure from European settlers to sell their land for settlement leading to the New Zealand wars.

The Whangaparaoa Peninsula was part of a purchase by the Crown known as the Mahurangi Purchase. Negotiations began in 1841 with the final sale not completed until 1854 but in this settlement the Crown gave various tribal groups cash and goods to the value of approximately GBP1,500 for land that extended from Te Arai to Takapuna and covered an area of 100,000 acres.

One of the early families in Whangaparaoa were the Glanville family. In 1857 Henry and Mary Glanville and their family arrived from New South Wales and settled in what is today known as Stanmore Bay. The bay became known as Glanville’s Bay. The family worked hard but struggled with clearing bracken fern and planted corn and wheat and fished for pilchards and they cultivated a fine vegetable patch and enjoyed dining on wild pigeons and ducks.

Unfortunately, Henry, who had emigrated because of a bad heart, died not long after their arrival and Mary returned to NSW. Henry was buried and his grave has never been found although his gravestone was discovered in the 1970’s in the bay. There is now a small cemetery in Stanmore Bay however it is believed Henry was probably buried closer to the homestead further down the bay.

In 1878 the younger Henry Glanville returned to NZ and sold the property to the Hill family who gave it the name Stanmore Bay after their home in Great Stanmore, England. The family never lived there but employed a farm manager to run the farm which ran along the 2 km beach. Stanmore Cottage still stands at the top of Brightside Road and is currently a childcare centre.

Another family who moved to the area in the 1850’s was the Polkinghorne family. Taking up a Crown Grant at the Wade in 1856 William Polkinghorne and his family moved, in 1877, to the beach now known as Manly. The bay was named Polkinghorne’s Bay. The name was changed to Manly in the 1920’s when two developers, Laurie Taylor and Bill Brown started sub-dividing the land and borrowed the name Manly from the bay in Sydney.

Waiau is the name for the combination of the 3 bays stretching from Swann Beach, Big Manly and Tindalls Bay and the names Big Manly and Little Manly began use as the areas started attracting visitors in the 1920’s. After an objection in the 1970’s however by a member of the Polkinghorne family the name Polkinghorne Bay was retained for the area of Waiau covering Big Manly and Swann Beach.

Swann Beach takes it’s name from another early landowner Percy Swann.

In 1859 William and Anne’s youngest son, William the younger was born. After his parents’ death William the younger remained in the area and in 1916 he built a cheese factory as well as the Post Office store. Unfortunately, the cheese factory was not a success and closed after 2 years of operation.

The Shakespear family were also one of the original families on the Peninsula. Purchasing the land in the 1880’s now known as Shakespear Regional Park. The Shakespear family were farmers who sold watermelons in Auckland city for many years. There is a classic yacht now owned by The Classic Yacht Charitable Trust, the “Frances” which became famously known as the “watermelon” boat. A workboat for the Shakespear family from 1908 to 1991, for many decades she would be seen arriving at Auckland’s then busy downtown market area with produce from the family farm at the end of the Peninsula (now Shakespear Regional Park) and departing with supplies for farming operations. In those times the three and a half-hour sailing trip was much to be preferred over the time-consuming and tortuous road alternative.

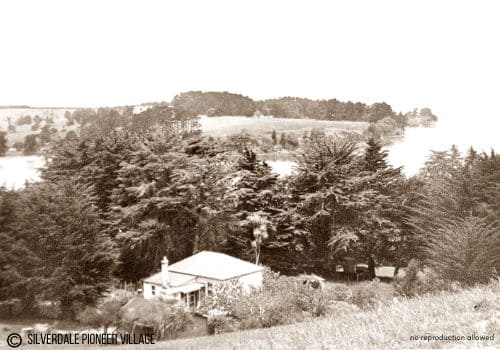

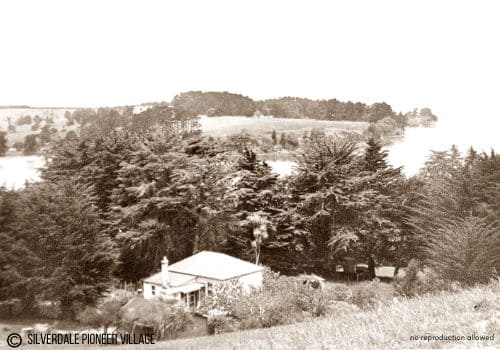

The land that the family ran as cattle, sheep and produce farm was purchased by Robert Shakespear’s grandfather, Sir Robert North Collie Hamilton, Baronet of Stratford on Avon, from Ranulph Dacre. The 1333-acre property on which the homestead was built passed to Blanche Shakespear after Sir Robert’s death.

Robert and Blanche had seven children, five of whom kept the farm going after their father’s death in 1910. Son Bob managed the operation with eldest daughter Frances (Cis), while Ivy, Ruby (Judy) and Ethel worked on the farm. Helen trained as a midwife and the youngest, Kitty, attended school in Auckland.

The Shakespear homestead was built on the site of a former Maori Pa site overlooking Te Haruhi Bay and remains of the pa, including a kumara pit, can still be seen in front of the house.

The lease on the property was taken over in 1983 by the YMCA who now run it as a lodge for local youth taking part in outdoor education programmes.

Matakatia was originally the name of a pa above the bay. Originally known as Tindalls Bay as that was where William Tindall had his home, the name Matakatia has only been in use since the 1940’s. The small island off the coast, Kotanui Island, described by Maori as a kota nui (big cockleshell), Pakeha settlers saw it as a Frenchman’s Cap, possibly influenced by the nationality of an early settler in the area.

The Hopper family came to Whangaparaoa in 1927 and Ken and Edith took over the store built by William Polkinghorne on the hill between Manly and Arkles.

Another early settler in the area was William Laing Thorburn who was the original European owner of Arkles Bay. He purchased the land in 1854. The original homestead was purchased by George Arkle in 1878 and it was George and Andrew, his brother, who divided the bay. George built a high tide wharf at the north eastern end of the bay and when Andrew built a guest house at his end the brothers fell out. A second wharf was subsequently built at Andrew’s southern end of the bay in 1923 (12 years after Andrew’s death).

In the 1920’s Whangaparaoa became a popular holiday destination with ferries coming across to Arkles Bay. This also opened up the land for more family investments.

Sales of land were slow and not helped by the Depression of the 1930s even though the availability of food from the land and fish from the sea meant locals were often better off than their Auckland counterparts where riots occurred on Queen Street in 1932.

The post-war years saw the bach bonanza of the 1950s when sections were sold in places like Stanmore Bay for the princely sum of £30 a pop (cheap even by the standards of the day). Hundreds of do-it-yourself Kiwis staked their claim and worked from dawn to dusk with whatever materials they could lay their hands on after the war to build the family bach.

By the end of the 60s there were about 2000 people living permanently on Whangaparaoa. This number would swell to over 25,000 in the summer as holidaymakers packed into baches and spare sections along the peninsula.

In the 1970s ad hoc development caught up with the Waitemata County Council. They tried to deal with an influx of people into the “Northern Beaches’ as they called this area with very basic sewerage ‘systems’ but these moves were fiercely rejected by locals and building was limited.

What followed in the 80s was coined the ‘Californication’ of Whangaparaoa as cross leasing and large scale developments hit the peninsula. There were calls for political independence as residents asked if this was the sort of progress they really wanted. In the 1990s development clicked into another gear with a corresponding surge of discontent. The Rodney District Council was referred to by one community leader as an “…incompetent, spendthrift bureaucracy, totally discredited and beyond recall.”

There have been further development spikes and troughs since then but what is remarkable is that the essential beauty of the Coast has remained intact despite the ravages of development and poor council planning. Indeed some parts of the Coast remain relatively unchanged from the last century, albeit due to geographic constraints and previously generous reserve acquisitions.

In the face of rapid intensification and population growth these locations are now invaluable legacies that we must preserve for future generations. They are, after all, what defines the uniqueness of this special place where we live.